Aging Clocks

Contents

6. Aging Clocks#

In this chapter, you will learn:

How to conduct clinical trials for anti-aging drugs ten times cheaper and faster.

The results of the last ten years of research on aging clocks.

How to use aging clocks to find new in silico geroprotectors.

Which aging clocks are the most accurate. Which are the cheapest.

Why not everything is straightforward and what else needs to be done in this area.

During the practice, you will create your own aging clocks using machine learning.

Contents

6.1. What is it#

Imagine that a genie gives you a magic device that shows people’s health as a number from zero to one hundred. For healthy young people, the device shows 100. Over time, the number decreases and when it reaches zero, the person dies. How could such a device be used?

First, it could speed up and cheapen clinical trials. If you are looking for a geroprotector, the primary endpoint of the trial is lifespan. People live on average 72 years, so it takes a lot of money and time to do the research, so you have all the chances to die yourself before you get the results. For example, now funds are being raised for the TAME [Barzilai et al., 2016] clinical trial of metformin for aging. In the last seven years, TAME – Targeting Aging with Metformin – has raised only 11 million dollars out of the necessary 40, and patient observation will last 6 years. If we had such a magic device, we wouldn’t necessarily have to wait so long. Instead of the primary endpoint (prolonging lifespan), we could use a surrogate endpoint. If the device shows an improvement in health, this would be a good sign that the geroprotector is working and we could stop the trial earlier. This would save money and time.

Secondly, the magic device would help us search for new interventions against aging. For example, we could collect a large dataset of device readings for different people and try to find associations between lifestyle and better health. Or if our magic device is a computer program that predicts a person’s health based on their indicators, we could run an optimization process: we would select such indicators to maximize health, and then find a way to similarly change human indicators. We will see how this idea helped find new geroprotectors that extended the life of worms [Janssens et al., 2019].

This magical device, referred to as a biological clock or aging clock, has been the primary focus of research in the field of the biology of aging in the past decade. It is usually a statistical model trained to predict a person’s chronological age based on their parameters, such as blood tests. The model is not perfect, so the predicted number differs from the actual chronological age. This prediction is called biological age and it is assumed that the error of the model is explained by the person’s health. A sick smoking person has a higher biological age than chronological age, while a healthy athlete has a lower biological age. The difference between biological and chronological age is called biological age acceleration.

Note

Chronological age is the number of years a person has been alive since their birth.

Biological age is a number that signifies a person’s health. In practice, this is a prediction of a model trained to predict chronological age.

Biological age acceleration is the difference between biological and chronological age.

6.2. Types of Biological Clocks#

The most common causes of death in developed countries are cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. These diseases have different mechanisms, but the strongest risk factor for all of them is age, so researchers of aging believe that aging is not just an association but a cause of many diseases, so slowing aging would reduce the likelihood of illness. This is called the geroscience hypothesis.

Note

The geroscience hypothesis proposes that aging is the primary cause of many chronic diseases, and that these diseases can be delayed by slowing down aging.

Aging biomarkers are an important focus of research in the field of aging because what cannot be measured cannot be improved. There are several key characteristics that are desirable for clinical use [Butler et al., 2004]:

They change with age;

They predict mortality better than chronological age;

They predict the early stages of age-related diseases;

They are minimally invasive and do not require painful or serious procedures.

In addition to these characteristics, Alexey Moskalev [Moskalev, 2019] also adds that ideal aging biomarkers should be:

Sensitive to early stages of aging;

Have predictability with collecting in the foreseeable time range;

Robust.

Over the years, dozens of biological clocks have been published. Here are the main types.

6.2.1. Epigenetics Clocks#

During transcription, RNA is produced based on the DNA sequence, which usually leads to protein synthesis. Different proteins are required under different conditions, so there are different ways to control transcription. One of these methods is DNA methylation, in which a methyl group is attached to a nucleotide, which typically leads to suppression of transcription.

In mammals, methylation usually occurs in special DNA regions consisting of “CG” nucleotides, called CpG sites. The average level of cytosine methylation in these regions can be experimentally measured as a number between 0 and 1, where 1 means that all cytosines in the site are methylated on both alleles and 0 means that all cytosines are unmethylated.

Note

CpG site – a cytosine nucleotide followed by a guanine nucleotide, forming the pattern “CG”. In mammals, 70-80% of cytosines in these regions are methylated, and conversely, a large portion of methylated nucleotides lie in these regions.

CpG island – a region of DNA with a high number of CpG sites.

Note

Most biological clocks work on bulk data, where only the average level of methylation is known, but single-cell methods are now available that can measure the methylation status of each nucleotide [Trapp et al., 2021].

As one ages, methylation changes in a complex, partly predictable way [Palumbo et al., 2018]. This means that the level of methylation can be used to predict a person’s age. Many clocks have been built on this idea. Let’s consider the most notable works.

6.2.1.1. 2011 Epigenetic predictor of age#

In [Bocklandt et al., 2011], the authors built the first epigenetic clock using saliva.

6.2.1.2. 2013 Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates#

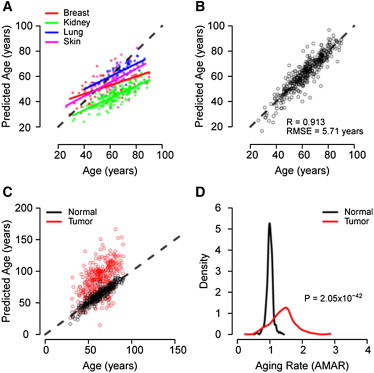

In [Hannum et al., 2013], the clock was built on blood cells. The authors analyzed the results and found that:

Men age 4% faster than women.

Clocks built on blood cells also work on other tissues, such as lung or kidney cells.

The authors confirmed the existence of epigenetic drift. The methylation of elderly people differs from each other more strongly than among young people. This is due to the accumulation of random errors.

Note

Epigenetic drift – An increase in methylation diversity with age: elderly people differ more from each other than young people. This is due to the accumulation of random errors.

Fig. 6.1 [Hannum et al., 2013]. Predictions for different tissues.#

6.2.1.3. 2013 DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types#

In [Horvath, 2013], the author:

Built clocks using different human tissues.

Showed that progerias (genetic diseases characterized by accelerated aging) increase biological age.

Showed that reprogramming cells into iPSCs resets biological age;

Showed that predictions of the clock in chimpanzee tissues correlate with chronological age;

Showed that cells that have undergone more divisions have a higher biological age.

Note

Progeria – a general term for rare genetic diseases characterized by accelerated aging.

6.2.1.4. 2018 An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan (PhenoAge)#

Ordinary biological clocks are trained to predict chronological age, expecting the model error to explain the mortality difference. But where does this assumption come from? If we could train a perfect oracle model that always correctly predicted chronological age, such a model would be useless. That is why we could predict how many years a person has left to live instead of chronological age.

In [Levine et al., 2018] the authors first trained a Cox proportional regression model to predict mortality using clinical biomarkers and age from the NHANES database. With it, they made a prediction for a dataset with blood methylation, and then trained the model to directly predict mortality from methylation data.

Acceleration of such a phenotypic epigenetic age is positively associated with mortality – an important property that was not present in previous clocks, so such clocks are called second generation clocks.

6.2.1.5. 2019 DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan#

The GrimAge[Lu et al., 2019] clock was constructed in a similar manner. As proxies for predicting mortality, the authors took the concentration of blood proteins and the number of smoked cigarette packs, which were predicted from methylation. As a result, a model was obtained that better predicted the date of death and the onset of age-related diseases than previous models.

Oracle Model

In [Zhang et al., 2019] the authors trained the most accurate epigenetic clocks with an RSME error of 2.04 years. While the model performed better than all previous ones, its acceleration of biological age no longer predicted mortality and was no longer associated with diseases, rendering clinical use of such clocks meaningless.

6.2.2. Other Clocks#

6.2.2.1. Transcriptomic Clocks#

DNA transcription is the process by which mRNA molecules, which are used to create proteins, are synthesized. By analyzing the full transcriptome, or all of the RNA molecules, of a cell, we can sequence and compare the transcriptomes of healthy individuals with those of sick individuals. This helps to uncover the mechanisms behind diseases and potentially discover new treatments[Yang et al., 2020].

We could learn more about aging by comparing the transcriptomes of old people with those of young people. One way to do this is to build aging clocks on the transcriptome and try to understand why the model turned out to be that way. This is what was done in [Mamoshina et al., 2018], where the authors trained clocks on the transcriptomes of human muscles. The clocks were less accurate (MAE 6.19 years) than methylome-based clocks, but feature importance techniques proposed new targets for potential geroprotectors.

In addition to interpretability, transcriptome-based clocks have another advantage. C. elegans roundworms do not have 5mC nucleotides, so epigenetic clocks cannot be built for them in the traditional sense. Therefore, transcriptome-based clocks were built for c. elegans [Meyer and Schumacher, 2021, Tarkhov et al., 2019] that work for worms of different strains living in different conditions.

6.2.2.2. Blood Test Clocks#

Transcriptome and methylome are obtained through expensive sequencing. It would be more convenient for clinical practice to build an aging clock on cheap complete blood count. This was done in [Putin et al., 2016], and the feature importance technique showed that the most important predictors of age are albumin, glucose, alkaline phosphatase, urea, and erythrocytes. The model can be conveniently used through the website http://aging.ai.

In the following article [Mamoshina et al., 2018], the authors improved the accuracy of the model and reduced the number of necessary measurements. The authors found that the quality of the model varies between patients from different countries: Canada, Eastern Europe, and South Korea.

6.3. Application of Biological Clocks#

Acceleration of biological age meets the criteria for a marker of aging. For example, it predicts mortality from various causes[Marioni et al., 2015]. An increase in epigenetic clock of the first generation is not associated with a deterioration of physical and cognitive functions[Marioni et al., 2015], but is associated for clocks of the second generation[Maddock et al., 2020].

Obesity [Horvath et al., 2014] and Down syndrome [Horvath et al., 2015] increase biological age. HIV also increases biological age even in brain tissue, although it is not clear why [Horvath and Levine, 2015].

In 2006, the CMAP dataset was published [Lamb et al., 2006], in which the authors measured how the transcriptome of cells changes after exposure to 1300 different drugs. Using this dataset and biological clocks, it is possible to find new drugs. For this, in [Janssens et al., 2019] the authors trained transcriptomic clocks on 51 human tissue and then searched in CMAP for drugs that, according to the model, reduce biological age. As a result, known geroprotectors and several new molecules were found, which were tested on worms c. elegans. The experiment confirmed that inhibitors of the protein Hsp90 extend life.

6.3.1. Open Questions#

During the search for drugs that lower the predicted model age, we find geroprotectors that extend life. Does this mean a causal relationship? Can we call a molecule that reduces biological age a geroprotector, but for which a costly, long-term clinical trial has not yet been conducted that proves a reduction in mortality? There are several problems [Bell et al., 2019, Schork et al., 2022].

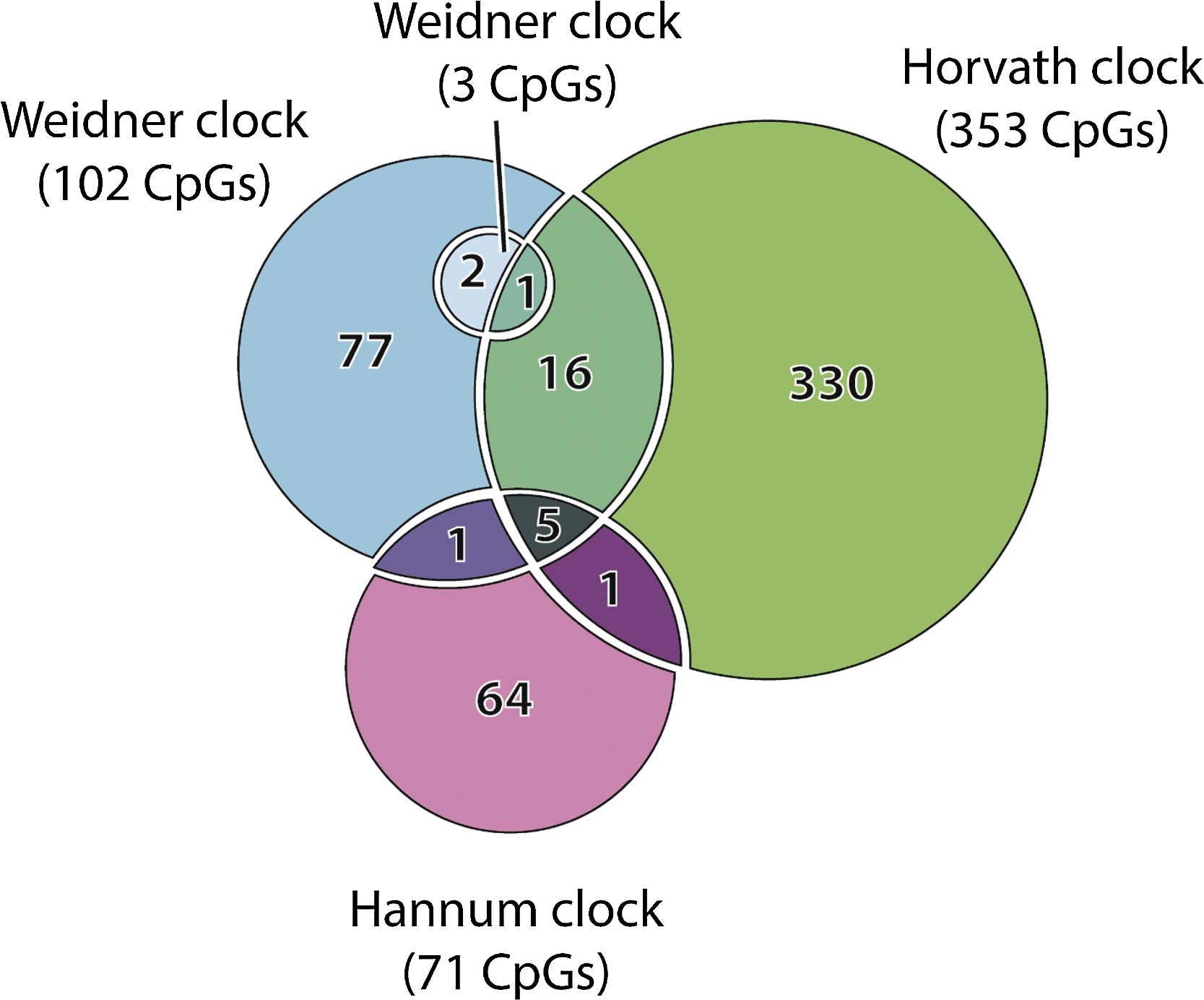

Predictions of different clocks are weakly correlated with each other. Epigenetic clocks are trained on different CpG sites.

Fig. 6.2 [Galkin et al., 2020]#

Does this mean that clocks measure different aspects of aging? Or that clock predictions are very noisy? The authors of [Liu et al., 2020] show that clocks capture different aspects of aging. If this is the case, it would be important to find these separate aspects and make separate clocks for them.

Predictions of aging clocks poorly correlate with other classic biomarkers, such as blood pressure or glucose levels. This may be because aging clocks only measure one aspect of aging, or because aging clocks measure something more fundamental than what other clinical biomarkers measure. Could molecules that reduce biological age but do not affect classic biomarkers extend lifespan?

The cause-and-effect relationship is unclear. To what extent are epigenetic changes the cause of aging, and to what extent are they a consequence? In the first generation of clock models, training was done on predicting chronological age. This means that the data on elderly people in the dataset are from those who have managed to live to old age. Could this distort the model?

The authors of [Nelson et al., 2020] show that it can. The authors simulated random changes in methylation and assumed two things: mortality increases with the number of changes in CpG sites and changes in different CpG sites increase mortality differently. They trained an Elasticnet model on synthetic data and showed that as a result of L1 regularization, it selects non-causative sites that contribute little to mortality

F.A.Q.

Q: Is it true that epigenetic clocks simply show differences in tissue composition?

A: It depends on the clock. If it is a multi-tissue [Horvath, 2013], then no: you can train the clock on one tissue and it will work on another. If it is a second generation [Levine et al., 2018, Lu et al., 2019] phenotypic clock or a single-tissue clock, then it is possible.

Q: Could it be that epigenetic clocks work only because they distinguish senescent cells?

A: It does not seem so, because they work in immortal non-senescent cells, such as immortalized B cells or in embryonic cells. Cell aging and senescence are associated, but they are not the same. See the discussion and experiments in [Lowe et al., 2016].

Q: Could it be that epigenetic clocks only measure the number of cell divisions?

A: It does not seem so, because they work in non-proliferating cells, such as brain cells.

6.4. Linear Regression#

As we can see, developing biological clocks is an important task in aging biology. Most biological clock models predict either chronological age or risk of death based on a person’s parameters. But how does this technically happen? How can we make our own biological clocks for our own data?

Almost all biological clocks are linear regression. Linear regression is ubiquitous, so we assume that the reader is already familiar with it, so we will only remind you of the main ideas. For a first introduction to linear regression, we recommend practical tutorials[1], [2], [3].

In the linear regression model, we assume that the predicted value is linearly dependent on the input data. Let \(y\) be the chronological age that we are trying to predict. \(x_{1}, x_{2}, \dots x_{n}\) are known input parameters, such as blood test results. Then in the linear regression model, we approximate \(y\) as a linear function:

where \(a_1, a_2, \dots a_n\) are coefficients that we need to select, and \(\epsilon\) represents normal noise, explaining, for example, that blood tests are measured with error:

We want to select such coefficients \(a_1, a_2, \dots a_n\) so that the model predicts chronological age as accurately as possible. In other words, we want to minimize the error:

In practice, the error is minimized using gradient descent, where at each iteration the coefficients \(a_1, a_2, \dots a_n\) are shifted in such a way as to make the error as small as possible.

6.4.1. Overfitting and Regularization#

The more parameters a model has, and the less data in the training dataset, the easier it is for the model to simply memorize the entire training dataset. In this case, the linear function approximating chronological age will poorly describe the real world, and we will see a large error on the test dataset. This is called overfitting and can easily occur if you have a small dataset and a large number of parameters.

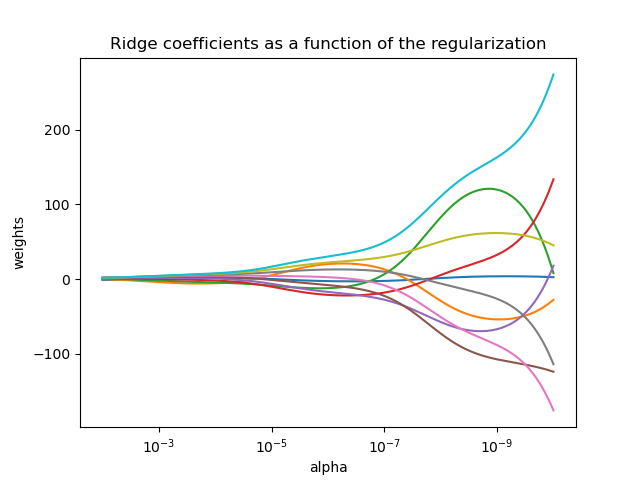

To deal with overfitting, regularization can be applied – that is, imposing some constraints to make the model simpler. For example, if you overfit a linear regression model, you will notice that its coefficients become very large:

It is unlikely that chronological age depends on blood test analyses with such coefficients in real life, so you can try penalizing the model for having too large coefficients during training. To do this, during gradient descent we will minimize both the error and the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients.

where \(\lambda\) is a coefficient representing the strength of regularization. This method of regularization is called L1 regularization and can improve the model’s performance on the test dataset in practice.

6.4.2. L1 and L2 regularization#

A model can be regularized in different ways, but the two most common methods are L1 and L2 regularization. L2 regularization differs in that the error is not just the absolute value of the coefficients, but also their squares added to the error:”

Both regularization methods help to find small coefficients, but the difference between them is that L2 regularization more heavily penalizes large coefficients and less heavily penalizes small coefficients. For example, if the model has two coefficients of 0.5 and 2, then with L2 regularization their contribution to the penalty becomes 0.25 and 4.

Both methods help to combat overfitting, but L1 is also useful in that the coefficients of unimportant features can quickly become zero, which gives us a useful signal that this blood parameter does not help the model predict chronological age. In practice, the regularization that helps improve the model’s performance on the test dataset is used.

Fig. 6.3 Effect of L1-regularization on the coefficients. The more penalty coefficient (alpha in picture), the less the coefficients. From sklearn tutorial.#

6.4.3. Elasticnet#

You can choose not to choose between the two regularization methods and simply apply both. Sometimes this works better than one regularization alone:

Such a model is called ElasticNet and is used in the construction of several clocks.

6.5. Conclusion#

Aging clocks are an important area of research that has the potential to greatly improve our understanding of the aging process and lead to the development of interventions to promote healthy aging. These clocks are biological markers that can be used to measure and predict the biological age of an individual. They can be based on a variety of factors, such as epigenetic modifications, blood tests, and gene expression patterns. While there has been significant progress in understanding and utilizing aging clocks, there are still many open questions and areas for further research.

One important aspect of aging clock research is the use of statistical analysis to make these clocks. Linear regression is a commonly used statistical method in this context, as it allows researchers to identify correlations and trends in the data. However, it is important to recognize that basic linear regression has limitations and additional regularizations may be necessary in certain circumstances.

Overall, the study of aging clocks has the potential to provide insights into the underlying mechanisms of aging and may lead to the development of interventions that can promote healthy aging and extend the human lifespan. While there is still much to learn about aging clocks and the aging process, the potential benefits of this research make it an important area of study for the scientific community.

6.6. Credits#

This text prepared by Simon Steshin.

- 1

Nir Barzilai, Jill P Crandall, Stephen B Kritchevsky, and Mark A Espeland. Metformin as a tool to target aging. Cell metabolism, 23(6):1060–1065, 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.011.

- 2

Christopher G Bell, Robert Lowe, Peter D Adams, Andrea A Baccarelli, Stephan Beck, Jordana T Bell, Brock C Christensen, Vadim N Gladyshev, Bastiaan T Heijmans, Steve Horvath, and others. Dna methylation aging clocks: challenges and recommendations. Genome biology, 20(1):1–24, 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1824-y.

- 3

Sven Bocklandt, Wen Lin, Mary E Sehl, Francisco J Sánchez, Janet S Sinsheimer, Steve Horvath, and Eric Vilain. Epigenetic predictor of age. PloS one, 6(6):e14821, 2011. URL: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014821.

- 4

Robert N Butler, Richard Sprott, Huber Warner, Jeffrey Bland, Richie Feuers, Michael Forster, Howard Fillit, S Mitchell Harman, Michael Hewitt, Mark Hyman, and others. Aging: the reality: biomarkers of aging: from primitive organisms to humans. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 59(6):B560–B567, 2004. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.6.b560.

- 5

Fedor Galkin, Polina Mamoshina, Alex Aliper, João Pedro de Magalhães, Vadim N Gladyshev, and Alex Zhavoronkov. Biohorology and biomarkers of aging: current state-of-the-art, challenges and opportunities. Ageing Research Reviews, 60:101050, 2020. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2020.101050.

- 6(1,2)

Gregory Hannum, Justin Guinney, Ling Zhao, LI Zhang, Guy Hughes, SriniVas Sadda, Brandy Klotzle, Marina Bibikova, Jian-Bing Fan, Yuan Gao, and others. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Molecular cell, 49(2):359–367, 2013. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016.

- 7(1,2)

Steve Horvath. Dna methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome biology, 14(10):1–20, 2013. URL: https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115.

- 8

Steve Horvath, Wiebke Erhart, Mario Brosch, Ole Ammerpohl, Witigo von Schönfels, Markus Ahrens, Nils Heits, Jordana T Bell, Pei-Chien Tsai, Tim D Spector, and others. Obesity accelerates epigenetic aging of human liver. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(43):15538–15543, 2014. URL: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1412759111.

- 9

Steve Horvath, Paolo Garagnani, Maria Giulia Bacalini, Chiara Pirazzini, Stefano Salvioli, Davide Gentilini, Anna Maria Di Blasio, Cristina Giuliani, Spencer Tung, Harry V Vinters, and others. Accelerated epigenetic aging in down syndrome. Aging cell, 14(3):491–495, 2015. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12325.

- 10

Steve Horvath and Andrew J Levine. Hiv-1 infection accelerates age according to the epigenetic clock. The Journal of infectious diseases, 212(10):1563–1573, 2015. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiv277.

- 11(1,2)

Georges E Janssens, Xin-Xuan Lin, Lluís Millan-Ariño, Alan Kavšek, Ilke Sen, Renée I Seinstra, Nicholas Stroustrup, Ellen AA Nollen, and Christian G Riedel. Transcriptomics-based screening identifies pharmacological inhibition of hsp90 as a means to defer aging. Cell reports, 27(2):467–480, 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.044.

- 12

Justin Lamb, Emily D Crawford, David Peck, Joshua W Modell, Irene C Blat, Matthew J Wrobel, Jim Lerner, Jean-Philippe Brunet, Aravind Subramanian, Kenneth N Ross, and others. The connectivity map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. science, 313(5795):1929–1935, 2006. URL: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1132939.

- 13(1,2)

Morgan E Levine, Ake T Lu, Austin Quach, Brian H Chen, Themistocles L Assimes, Stefania Bandinelli, Lifang Hou, Andrea A Baccarelli, James D Stewart, Yun Li, and others. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY), 10(4):573, 2018. URL: https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.101414.

- 14

Zuyun Liu, Diana Leung, Kyra Thrush, Wei Zhao, Scott Ratliff, Toshiko Tanaka, Lauren L Schmitz, Jennifer A Smith, Luigi Ferrucci, and Morgan E Levine. Underlying features of epigenetic aging clocks in vivo and in vitro. Aging cell, 19(10):e13229, 2020. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13229.

- 15

Donna Lowe, Steve Horvath, and Kenneth Raj. Epigenetic clock analyses of cellular senescence and ageing. Oncotarget, 7(8):8524–8531, 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.7383.

- 16(1,2)

Ake T Lu, Austin Quach, James G Wilson, Alex P Reiner, Abraham Aviv, Kenneth Raj, Lifang Hou, Andrea A Baccarelli, Yun Li, James D Stewart, and others. Dna methylation grimage strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY), 11(2):303, 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.101684.

- 17

Jane Maddock, Juan Castillo-Fernandez, Andrew Wong, Rachel Cooper, Marcus Richards, Ken K Ong, George B Ploubidis, Alissa Goodman, Diana Kuh, Jordana T Bell, and others. Dna methylation age and physical and cognitive aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 75(3):504–511, 2020. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz246.

- 18

Polina Mamoshina, Kirill Kochetov, Evgeny Putin, Franco Cortese, Alexander Aliper, Won-Suk Lee, Sung-Min Ahn, Lee Uhn, Neil Skjodt, Olga Kovalchuk, and others. Population specific biomarkers of human aging: a big data study using south korean, canadian, and eastern european patient populations. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 73(11):1482–1490, 2018. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly005.

- 19

Polina Mamoshina, Marina Volosnikova, Ivan V Ozerov, Evgeny Putin, Ekaterina Skibina, Franco Cortese, and Alex Zhavoronkov. Machine learning on human muscle transcriptomic data for biomarker discovery and tissue-specific drug target identification. Frontiers in genetics, 9:242, 2018. URL: https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2018.00242.

- 20

Riccardo E Marioni, Sonia Shah, Allan F McRae, Brian H Chen, Elena Colicino, Sarah E Harris, Jude Gibson, Anjali K Henders, Paul Redmond, Simon R Cox, and others. Dna methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome biology, 16(1):1–12, 2015. URL: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0584-6.

- 21

Riccardo E Marioni, Sonia Shah, Allan F McRae, Stuart J Ritchie, Graciela Muniz-Terrera, Sarah E Harris, Jude Gibson, Paul Redmond, Simon R Cox, Alison Pattie, and others. The epigenetic clock is correlated with physical and cognitive fitness in the lothian birth cohort 1936. International journal of epidemiology, 44(4):1388–1396, 2015. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu277.

- 22

David H Meyer and Björn Schumacher. Bit age: a transcriptome-based aging clock near the theoretical limit of accuracy. Aging cell, 20(3):e13320, 2021. URL: https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13320.

- 23

Alexey Moskalev. Biomarkers of human aging. Volume 10. Springer, 2019. URL: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-24970-0.

- 24

Paul G Nelson, Daniel EL Promislow, and Joanna Masel. Biomarkers for aging identified in cross-sectional studies tend to be non-causative. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 75(3):466–472, 2020. URL: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz174.

- 25

Domenico Palumbo, Ornella Affinito, Antonella Monticelli, and Sergio Cocozza. Dna methylation variability among individuals is related to cpgs cluster density and evolutionary signatures. BMC genomics, 19(1):1–9, 2018. URL: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-018-4618-9.

- 26

Evgeny Putin, Polina Mamoshina, Alexander Aliper, Mikhail Korzinkin, Alexey Moskalev, Alexey Kolosov, Alexander Ostrovskiy, Charles Cantor, Jan Vijg, and Alex Zhavoronkov. Deep biomarkers of human aging: application of deep neural networks to biomarker development. Aging (Albany NY), 8(5):1021, 2016. URL: https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.100968.

- 27

Nicholas J Schork, Brett Beaulieu-Jones, Winnie Liang, Susan Smalley, and Laura H Goetz. Does modulation of an epigenetic clock define a geroprotector? Advances in geriatric medicine and research, 2022. URL: https://doi.org/10.20900%2Fagmr20220002.

- 28

Andrei E Tarkhov, Ramani Alla, Srinivas Ayyadevara, Mikhail Pyatnitskiy, Leonid I Menshikov, Robert J Shmookler Reis, and Peter O Fedichev. A universal transcriptomic signature of age reveals the temporal scaling of caenorhabditis elegans aging trajectories. Scientific reports, 9(1):1–18, 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43075-z.

- 29

Alexandre Trapp, Csaba Kerepesi, and Vadim N Gladyshev. Profiling epigenetic age in single cells. Nature Aging, 1(12):1189–1201, 2021. URL: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-021-00134-3.

- 30

Xiaonan Yang, Ling Kui, Min Tang, Dawei Li, Kunhua Wei, Wei Chen, Jianhua Miao, and Yang Dong. High-throughput transcriptome profiling in drug and biomarker discovery. Frontiers in genetics, 11:19, 2020. URL: https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.00019.

- 31

Qian Zhang, Costanza L Vallerga, Rosie M Walker, Tian Lin, Anjali K Henders, Grant W Montgomery, Ji He, Dongsheng Fan, Javed Fowdar, Martin Kennedy, and others. Improved precision of epigenetic clock estimates across tissues and its implication for biological ageing. Genome medicine, 11(1):1–11, 2019. URL: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-019-0667-1.